👋🏼 This is part of series on concurrency, parallelism and asynchronous programming in Ruby. It’s a deep dive, so it’s divided into several parts:

- Your Ruby programs are always multi-threaded: Part 1

- Your Ruby programs are always multi-threaded: Part 2

- Consistent, request-local state

- Ruby methods are colorless

- The Thread API

- Bitmasks, Ruby Threads and Interrupts, oh my!

- When good threads go bad

- Thread and its MaNy friends

- Fibers

- Processes, Ractors and alternative runtimes

- Scaling concurrency with streaming

- Abstracted, concurrent Ruby

- Closing thoughts, kicking the tires and tangents

- How I dive into CRuby concurrency

You’re reading “When good threads go bad”. I’ll update the links as each part is released, and include these links in each post.

Threads out after curfew 🧵

It’s late, and you start getting alerts that requests to your web server are failing. You try to load a page and it hangs endlessly. The server isn’t responding to anything, and requests are continuing to queue up.

It’s 10PM. Do you know where your

childrenthreads are?📺 iykyk

Not knowing what else to do, you trigger a server restart. Even doing that, things remain unresponsive for another 30 seconds. Finally you see the server stop, and start up again. As if by magic, everything is running fine again.

You’re running Puma with threads. It seemed like every thread was unresponsive. What happened to those threads?!

Stuck threads

The reality of the situation is probably mundane.

- Are you looking up data in a query? Did you remember to index your columns?

- Do you have N+1 queries?1

- Did you remember to set statement and lock timeouts before running a schema migration?

- Are you sure it isn’t 1, 2 or 3?

If it isn’t those things, there are other ways your threads can go rogue. Let’s look at some ways a thread can get stuck:

- Deadlocks

- Livelocks

- Long-running CPU

- Long-running IO

- Native extensions

Deadlocks

The conventional example of a deadlock is two threads attempting to acquire a mutexheld by the other thread.

They can never make progress, so they’re dead in the water:

mutex_1 = Mutex.new

mutex_2 = Mutex.new

thread_1 = Thread.new do

mutex_1.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_2.lock

end

end

thread_2 = Thread.new do

mutex_2.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_1.lock

end

end

thread_1.join

In our example, thread_1 acquires mutex_1. Then thread_2 acquires mutex_2. Next, thread_1 attempts to acquire mutex_2 and blocks. Then thread_2 attempts to require mutex_1 and blocks. Neither can make progress, and are stuck in place.

It’s a traditional example, but Ruby is very good at detecting it! It detects the problem and raises an error, checking if any threads are capable of making progress:

'Thread#join': No live threads left. Deadlock? (fatal)

3 threads, 3 sleeps current:0x0000000a35e90c00 main thread:0x0000000101262de0

* #<Thread:0x00000001001fafa8 sleep_forever>

rb_thread_t:0x0000000101262de0 native:0x0000000202cfc800 int:0

* #<Thread:0x0000000121727c08 (irb):101 sleep_forever>

rb_thread_t:0x0000000a35e90e00 native:0x00000001700f7000 int:0 mutex:0x0000000a3638c000 cond:1

depended by: tb_thread_id:0x0000000101262de0

* #<Thread:0x00000001217279d8 (irb):107 sleep_forever>

rb_thread_t:0x0000000a35e90c00 native:0x0000000170203000 int:0

Ruby detects that thread_1 and thread_2 are sleeping, and the third thread is Thread.main, which sleeps waiting for thread_1 to finish.

Most long running programs are likely to have some other thread running, and Ruby only detects if all threads are stuck. We can get our deadlock example to work by adding an extra thread in a work loop:

mutex_1 = Mutex.new

mutex_2 = Mutex.new

thread_1 = Thread.new do

mutex_1.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_2.lock

end

end

thread_2 = Thread.new do

mutex_2.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_1.lock

end

end

thread_3 = Thread.new do

loop do

# process some work...

end

end

thread_1.join

Now threads 1 and 2 will never progress, and Ruby lets the program continue running because thread_3 is still active.

Livelocks

While a deadlock means a thread has stopped processing, a livelock happens when a thread keeps running, but never makes any progress. Here’s another example using an alternative approach for acquiring a mutex:

mutex_1 = Mutex.new

mutex_2 = Mutex.new

thread_1 = Thread.new do

mutex_1.synchronize do

sleep 0.1

while !mutex_2.try_lock; end

end

end

thread_2 = Thread.new do

mutex_2.synchronize do

sleep 0.1

while !mutex_1.try_lock; end

end

end

thread_1.join

This is similar to our deadlock example, but this time we use #try_lock instead of #lock. Unlike #lock, which blocks until the mutex is available, #try_lock returns false if attempting the lock fails. We do a short sleep in each thread to give them time to acquire the initial locks, then iterate infinitely attempting #try_lock. The locks will never be acquired, and the loops will run forever. Burn, CPU, burn 🔥.

Personally I’ve rarely encountered deadlocks and livelocks in threaded code. But I’ve definitely encountered them in databases!

thread_1 = Thread.new do

User.find(1).with_lock do

sleep 0.1

User.find(2).lock!

end

end

thread_2 = Thread.new do

User.find(2).with_lock do

sleep 0.1

User.find(1).lock!

end

end

thread_1.join

On PostgreSQL, it will detect this deadlock and raise an error:

PG::TRDeadlockDetected: ERROR: deadlock detected (ActiveRecord::Deadlocked)

DETAIL: Process 581 waits for ShareLock on transaction 4003; blocked by process 582.

Process 582 waits for ShareLock on transaction 4002; blocked by process 581.

CONTEXT: while locking tuple (0,1) in relation "users"

How do we solve deadlocks and livelocks? The answer is a consistent order for locking.

mutex_1 = Mutex.new

mutex_2 = Mutex.new

thread_1 = Thread.new do

mutex_1.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_2.lock

end

end

thread_2 = Thread.new do

mutex_1.synchronize do

sleep 1

mutex_2.lock

end

end

thread_3 = Thread.new do

loop do

# process some work...

end

end

thread_1.join

This is the same example as before, but this time both threads attempt to acquire mutexes in identical order. As long as you acquire in a consistent order, you should never hit deadlocks or livelocks.

Long-running CPU

As far as I know, this isn’t actually possible in pure Ruby. What I mean by “pure” Ruby is a program that only runs Ruby code, and no C/Rust/Zig extensions. The CRuby runtime controls how pure Ruby code runs, and makes sure we can’t hog threads. Mostly.

In Bitmasks, Ruby Threads and Interrupts, oh my!, we dug into the TIMER_INTERRUPT_MASKand how it utilizes priority. It allows a thread to influence how large of a time slice it gets:

def calculate_priority(priority, limit)

priority > 0 ? limit << priority : limit >> -priority

end

calculate_priority(0, 100) # => 100ms

calculate_priority(2, 100) # => 400ms

calculate_priority(-2, 100) # => 25ms

At a default priority of 0, we get Ruby’s default time slice of 100ms. At -2, we get 25ms. At 2, we get 400ms. This means in theory, can we starve out other threads by increasing our priority?

calculate_priority(5, 100) # => 3276800ms

3,276,800 milliseconds is 54 minutes. Can we really block things for 54 minutes!?

counts = Array.new(10, 0)

done = false

threads = 10.times.map do |i|

Thread.new do

j = 0

loop do

break if done

j += 1

counts[i] += 1 if j % 1_000_000 == 0

end

end.tap do |t|

t.priority = 15 if i == 5

end

end

sleep 10

done = true

counts.each_with_index { |c, i| puts "#{i}: #{c}" }

There’s a bunch going on here - but there are only a few details to focus on:

- For the 6th thread (

i == 5), we set the priority to 15. That’s the priority that in theory gives us a time slice of 54 minutes. - We set a count every million iterations in each thread.

- We sleep for 10 seconds, then set a killswitch on each thread by setting

donetofalse. - We print how many times each thread was able to increment their slice of the array.

Here’s the output:

0: 26

1: 27

2: 26

3: 27

4: 28

5: 189

6: 24

7: 24

8: 24

9: 24

As we can see - the priority made a difference! The thread at index 5 runs around 7 times as much as every other thread. But, it does not fully hog the thread like we might have thought. This is only 10 seconds, well under 54 minutes, and the other threads still get prioritized by the scheduler.

This shows that we can influence the scheduler, but we can’t completely hog the runtime from pure Ruby code.

In more practical Ruby code, the Sidekiq gem gives you the ability to set priority on the threads it creates:

Sidekiq.configure_server do |cfg|

cfg.thread_priority = 15

end

Interestingly, by default, Sidekiq sets its threads to a priority of -1, which is less than the 0 that Ruby uses by default. It describes the rationale:

Ruby’s default thread priority is 0, which uses 100ms time slices. This can lead to some surprising thread starvation; if using a lot of CPU-heavy concurrency, it may take several seconds before a Thread gets on the CPU.

Negative priorities lower the timeslice by half, so -1 = 50ms, -2 = 25ms, etc. With more frequent timeslices, we reduce the risk of unintentional timeouts and starvation.

Fascinating to see a real-world use-case of priority like this! Sidekiq has run trillions of jobs across hundreds of thousands of apps, and they made the decision to switch the priority.

Since Ruby 3.4, you can achieve the same thing globally by using RUBY_THREAD_TIMESLICE. You can set RUBY_THREAD_TIMESLICE=50 and keep the priority the same, but now the time slice is 50ms.

Long-running IO

This is the likeliest scenario that will saturate your threads: long-running IO. In Ruby methods are colorless, we discussed how threads are great at handing off work when blocked on IO:

As soon as you do any IO operation, it just parks that thread/fiber and resumes any other one that isn’t blocked on IO.

However, this only works as long as:

- You have other threads available to pickup work

- You’ve tuned your thread counts based on your workload. Amdal’s Law helps you decide how many threads you should run, based on how much IO is running in your code

Earlier we mentioned slow queries as a possible IO blocker. But let’s say you have a web server running with 5 threads, and you allow users to download files2:

class DownloadsController < ApplicationController

def index

send_file Rails.root.join("public/large.txt"),

filename: "large.txt",

type: "application/octet-stream"

end

end

We have a simple Rails controller action, which sends a file to the client making the request. It’s pretty straightforward! The large.txt file I tested with locally is about 130mb. I’ll run it in a basic Puma setup, using 5 threads:

bundle exec puma -t 5:5

Puma starting in single mode...

* Puma version: 7.1.0 ("Neon Witch")

* Ruby version: ruby 4.0.0 (2025-12-25 revision 553f1675f3) +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

* Min threads: 5

* Max threads: 5

I’m running a Puma server with 5 threads. Let’s try some benchmarks against it. We’ll use Apache Bench (ab) to simulate traffic to Puma. -n means the number of total requests, and -c is how many concurrent requests to make. Let’s start with 1 request:

ab -n 1 -c 1 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 1

Time taken for tests: 0.070 seconds

Complete requests: 1

Cool - 0.07 seconds. How about 3?

ab -n 3 -c 3 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 3

Time taken for tests: 0.074 seconds

Complete requests: 3

Not much change from a single request! How about 5? This would match the maximum number of simultaneous requests our server can currently support, using 5 threads:

ab -n 5 -c 5 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 5

Time taken for tests: 0.134 seconds

Complete requests: 5

Things slow down a little bit once we max out our threads. But still reasonable. How about 50?

ab -n 50 -c 50 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 50

Time taken for tests: 0.820 seconds

Complete requests: 50

So far, so good. But we’re benefiting from a lot here: the file isn’t particularly large, and there is no latency. The server is responding quickly, and the client is consuming the response quickly. Let’s switch things up a bit - how well does it handle a client downloading slowly?

We’ll use curl to simulate a slow client. We can use limit-rate to simulate a client downloading only 1000k per second. curl ... --limit-rate 1000k & means we’ll download results at a rate of 1000k per second, running in the background (&). This means it will take our curl call 2 or 3 minutes to download a 130mb file. At the same time, we’ll run another apache bench to see how things perform:

curl http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads -o /tmp/large.txt \

--limit-rate 1000k &

ab -n 1 -c 1 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 1

Time taken for tests: 0.056 seconds

Complete requests: 1

Puma responds quickly. In this scenario, curl is occupying one thread, and ab occupies another. Let’s try running 4 curl commands:

for i in {1..4}; do

curl http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads -o /tmp/large_$i.txt \

--limit-rate 1000k &

done

ab -n 1 -c 1 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 1

Time taken for tests: 0.059 seconds

Complete requests: 1

Puma still responds fine. curl is now occupying 4 threads, and ab uses the remaining 1 thread. Let’s add one more request using curl. We also increase the default timeout of ab (which is 30) to 200, for no particular reason…

for i in {1..5}; do

curl http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads -o /tmp/large_$i.txt \

--limit-rate 1000k &

done

ab -n 1 -c 1 -s 200 http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads

Concurrency Level: 1

Time taken for tests: 124.477 seconds

Complete requests: 1

Yikes. That did not go well. The moment we had 5 slow running requests from our curl calls, we saturated all available threads. Our 6th request using ab sat around waiting, finally finishing 2 minutes later!

This is a critical consideration - long-running web work is a throughput killer. Ideally, keep all work as fast as possible and offload long-running work to jobs/other services. Most commonly for a download you’d create a presigned url for a service like S3 and redirect to that URL.

If you need to run long-running IO, you need to allocate many more threads3.

Native extensions

In our Long-running CPU example, we couldn’t get pure Ruby code to completely hog the runtime. We can prioritize a thread higher than other threads, but work still continues to be distributed.

Once you start running native extensions, the Ruby runtime has more limited influence. It’s up to the extension to properly interface with Ruby and yield control back. Here’s a simple example that will block all other threads, using the standard openssl gem, using a function written in C, pbkdf2_hmac:

require "openssl"

Thread.new do

loop do

puts "tick #{Time.now}"

end

end

t = Thread.new do

loop do

OpenSSL::KDF.pbkdf2_hmac("passphrase", salt: "salt", iterations: 12_800_000, length: 32, hash: "sha256")

end

end

t.join

We have two threads running - one infinitely printing the time in a loop, and one infinitely calling pbkdf2_hmac in a loop. Here I give pbkdf2_hmac a ludicrous number of iterations to force the function to run, in C, for a long period of time:

tick 2025-12-29 15:20:30 -0500

tick 2025-12-29 15:20:45 -0500

tick 2025-12-29 15:20:59 -0500

The results show that despite each thread having the same priority, the thread with long-running C extension code hogs all of the runtime. The printing thread is able to print a timestamp roughly every 15 seconds.

There’s nothing the extension code is doing wrong per se, but because it runs purely in C, without yielding back to Ruby until its done, Ruby can’t do anything to keep work distribution fair.

In most cases, well-developed/mature native extensions won’t hit this issue. There are many popular gems that are, or include, native extensions. But if you do hit an expensive path in a C extension, be aware the Ruby runtime will not be able to control it. If you know you are interfacing with a slow piece of code in a native extension, keep it off the hot path, same as our long-running IO example.

What happened to our Puma server, anyways?

Remember our production panic scenario from earlier?

Not knowing what else to do, you trigger a server restart. Even doing that, things remain unresponsive for another 30 seconds. Finally you see the server stop, and start up again. As if by magic, everything is running fine again

You triggered a server restart, and still had to wait 30 seconds? Why wasn’t Puma able to stop sooner? Let’s reuse our download example from earlier, and explain some default Puma behaviors!

First, let’s start Puma, and see how quickly we can stop it:

bundle exec puma -t 5:5

Puma starting in single mode...

* Puma version: 7.1.0 ("Neon Witch")

* Ruby version: ruby 4.0.0 (2025-12-25 revision 553f1675f3) +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

* Min threads: 5

* Max threads: 5

### hit ctrl + c to issue a SIGINT signal

Gracefully stopping, waiting for requests to finish

=== puma shutdown: 2025-12-29 23:45:21 -0500 ===

- Goodbye!

We instantly see two things:

Gracefully stopping, waiting for requests to finishGoodbye!

Puma tells us it is shutting down “gracefully”. With no activity, it is able to instantly stop.

Now let’s use our DownloadController again:

class DownloadsController < ApplicationController

def index

send_file Rails.root.join("public/large.txt"),

filename: "large.txt",

type: "application/octet-stream"

end

end

We start Puma again, then occupy each thread with a request:

bundle exec puma -t 5:5

for i in {1..5}; do

curl http://0.0.0.0:9292/downloads -o /tmp/large_$i.txt \

--limit-rate 1000k &

done

Now let’s trying issuing INT using ctrl+c again:

Puma starting in single mode...

...

Use Ctrl-C to stop

^C <-- ctrl + c

... ~120 second pass, all downloads finish ...

- Gracefully stopping, waiting for requests to finish

=== puma shutdown: 2025-12-30 00:04:23 -0500 ===

- Goodbye!

Ok, so we issued our interruption. But… it waited for every request to completely finish! We had to wait around 120 seconds before our server shutdown. That’s even worse than earlier!

This isn’t a blog post about Puma specifically, but I’ll discuss a few factors:

- Running

puma -t 5:5puts you in Puma “single” mode. This is a lightweight way of running puma, at the cost of less control. By default, single-mode Puma does not kill any requests. Like it tells us, it simply is “waiting for requests to finish” - Alternatively, you can run puma in “cluster” mode. This is done by adding any worker count at all using the

-wflag. Even a-w 1will move you into cluster mode. Cluster mode has a parent worker which monitors and controls child workers. This costs more memory, but it means the parent worker can kill child workers more reliably

Let’s try this one more time, starting in cluster mode by setting -w 1:

bundle exec puma -t 5:5 -w 1

[39363] Puma starting in cluster mode...

[39363] * Min threads: 5

[39363] * Max threads: 5

[39363] * Master PID: 39363

[39363] * Workers: 1

[39363] Use Ctrl-C to stop

^C <-- ctrl + c

[45110] - Gracefully shutting down workers...

... ~30 second pass, downloads are cut early ...

[45110] === puma shutdown: 2025-12-30 00:24:21 -0500 ===

[45110] - Goodbye!

This time we replicate our earlier behavior - 30 seconds pass, and the server is shutdown. Now that we’re running in cluster mode, by default Puma uses a configuration called worker_shutdown_timeout, which defaults to 30 seconds. If you have a configuration file, you can set it yourself to something longer or shorter:

worker_shutdown_timeout 25 # instead of 30

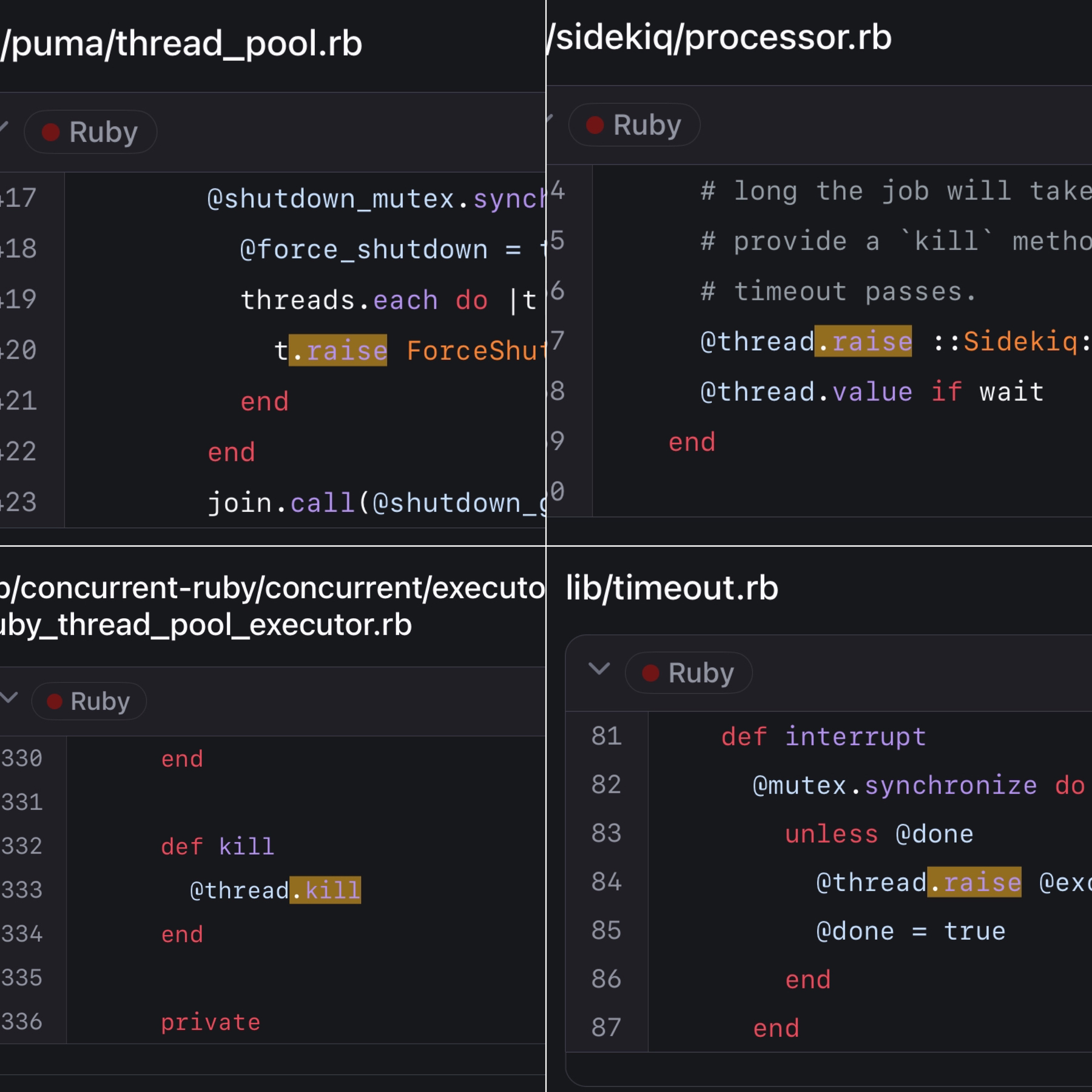

As well, by default Puma never kills threads. In a moment we’re going to be talking about ways to kill a thread. Puma plays it extremely safe, and offers no ability to kill individual threads. And even when shutting down, it defaults to a thread shutdown policy of :forever, which means the only way the threads are killed is when the server is entirely shutdown, which shuts down the worker the threads live in.

You can change this. In the same configuration file you’d set worker_shutdown_timeout you can set force_shutdown_after:

force_shutdown_after 1 # an integer, :forever, or :immediate

Still - this doesn’t do much. It still only impacts full server shutdown. But with this setting, the internal Puma thread pool will raise on all threads, and then eventually run kill on them.

What all this means is that by default in Puma:

- The primary way to fix misbehaving threads is to restart your server

- This will take up to 30 seconds running in cluster mode, unless you change the

worker_shutdown_timeout - Puma can’t kill long-running or stuck threads without a full server shutdown. Technically there is a control server you can setup, which can manage individual workers. But it cannot kill individual threads/requests

We’ll talk in-depth later about the available option for killing long-running threads in Puma.

📝 if you want to dig deeper into how Puma works, I highly recommend Dissecting Puma: Anatomy of a Ruby Web Server. The source of Puma is also pretty readable

Don't guess, measure

All of these thread issues are possibilities, but they mean nothing without empirical data. Measure, then decide your course of option.

Thread Shutdown

Ok, enough about how threads get stuck. Once they’re stuck - is there a way to stop them?

raise and kill

You want to kill… me? 🥺

⚠️ TL;DR You shouldn’t use these methods unless you really know what you’re doing. Instead, interrupt your thread safely. Incidentally, you should also avoid the timeout module.

if you’re writing a generic threaded framework you may need it - for custom one-off threads you can probably manage without it

Sometimes a thread is running and you need to shut it down. There’s two primary methods for achieving that: raise and kill.

raise will raise an error inside of the target thread. If the thread hasn’t started yet, in most cases it is killed before running anything:

t = Thread.new do

puts "never runs"

end

t.raise("knock it off")

sleep 0.01

puts thread_status(t)

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: knock it off", error=#<RuntimeError: knock it off>

📝

thread_statusis the helper we defined in the “Thread API” section onstatus

The error isn’t raised instantly - only at the point the thread is scheduled next. We sleep 0.1 to give thread t an opportunity to start. The thread scheduler starts it, and it immediately raises our “knock it off” error, effectively running right before puts "never runs".

If the thread gets a chance to start, the error will be raised on whatever line happened to be running last:

t = Thread.new do

sleep 5

end

t.join(1)

# We're only one second into the threads sleep at this point, so knock it off is raised from the `sleep 5` line

t.raise("knock it off, sleepyhead!")

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: knock it off, sleepyhead!", error=#<RuntimeError: knock it off, sleepyhead!>

Because it raises whatever error is provided (a RuntimeError if just a string is provided), we can actually rescue the error, ignore it, and retry 😱:

class KnockItOffError < StandardError; end

t = Thread.new do

sleep 5

puts "✌️"

rescue KnockItOffError => e

puts "Nice try #{e}"

retry

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

t.join

puts thread_status(t)

# Nice try 👊

# ✌️

#<ThreadStatus status="finished" error=nil>

With raise and kill, issues start to creep in when errors are thrown in an ensure. Here we use a ConditionVariable (we dug into those in The Thread API) to guarantee we raise from the ensure block:

mutex = Mutex.new

condition = ConditionVariable.new

t = Thread.new do

sleep 5

puts "✌️"

ensure

mutex.synchronize do

# Signal the condition.wait in the main thread

condition.signal

# ...perform some cleanup...

condition.wait(mutex)

puts "I'll never fire 😔"

end

end

mutex.synchronize do

# This will wait until our Thread ensure runs and signals us

condition.wait(mutex)

end

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

mutex.synchronize do

# We've enqueued our error, now signal so condition#wait fires in the ensure block

condition.signal

end

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊", error=#<RuntimeError: 👊>

We don’t see “I’ll never fire 😔”. What happens to our cleanup? Shouldn’t ensure, erm, umm, ensure that things finish…

Moving on from raise, kill stops the thread from running anymore instructions, no matter what it’s doing. raise can be rescue’d, kill can’t.

t = Thread.new do

sleep 5

puts "✌️"

# Exception is the root of the Error class hierarchy. If you can't rescue it with this, you can't rescue it

rescue Exception

puts "#kill cannot be stopped..."

ensure

puts "This will still run"

end

t.join(1)

t.kill

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# A #kill'd thread gives no indication it was terminated 😔

#<ThreadStatus status="finished", error=nil>

📝 Technically,

killcan be ignored, we’ll explain that when discussinghandle_interrupt.⚠️ Don’t rescue

Exception, it’s a bad idea and you could accidentally rescue things like an OutOfMemoryError 😬

Because kill doesn’t raise an error, you actually can’t even tell that the thread was killed. We just get the normal false status, represented in our example by “finished”.

Like raise, kill can also disrupt your ensure methods:

mutex = Mutex.new

condition = ConditionVariable.new

t = Thread.new do

sleep 5

puts "✌️"

ensure

mutex.synchronize do

condition.signal

# perform some cleanup

condition.wait(mutex)

puts "I'll never fire 😔"

end

end

mutex.synchronize do

condition.wait(mutex)

end

t.kill

mutex.synchronize do

condition.signal

end

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# ✌️

#<ThreadStatus status="finished" error=nil>

There are a few aliases for kill to be aware of as well:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.exit # internally gets the current thread, and calls `kill`

end

t2 = Thread.new { sleep }

Thread.kill(t) # class method `kill`

t2.exit # alias for `kill`

t2.terminate # alias for `kill`

Case closed. Feel free to use raise and kill on your threads. No harm no foul… oh what’s this here?

Ruby’s Thread#raise, Thread#kill, timeout.rb, and net/protocol.rb libraries are broken

Why Ruby’s Timeout is dangerous (and Thread.raise is terrifying)

The Oldest Bug In Ruby - Why Rack::Timeout Might Hose your Server

Timeout: Ruby’s Most Dangerous API

Oh…

Strangely, the thread docs say nothing about the dangers of these methods4. These articles are from 2008, 2015 and 2017. Surely no one uses it anymore, considering all that?

Nah.

In fairness to threaded gems that use these methods, they are using the official way you shutdown a thread. And they’re usually taking as many precautions as possible, prior to calling them. For the most part, gems use them as a shutdown mechanism, and give plenty of room for the thread to finish normally first.

The basic problem is this: raise and kill force your code to die at any point, with no guarantee of properly cleaning up.

You might ask: “Couldn’t ctrl+c do the same thing?”. Yes, an OS signal could kill your process or program before an ensure runs, but then all related state is also removed - it can cause other issues, but at least your program cannot limp along in a corrupted state.

ensure

# but, but Ruby - you _promised_ me this would run 😭

@value = false

end

So are they pure evil? An occasional necessity? Somewhere in between? I’ll leave that discussion to the code philosophers… in the practical realm, follow these rules:

📝 A small slice of this next section may look familiar. I included a bit of it in The Thread API. This goes much more in-depth

- Don’t use

Thread.kill,killorraiseunless you really, really know what you’re doing. Same applies for thekillaliasesexitandterminate - If you need to stop a thread, you want it to tear down safely. Make it safely interruptible by adding in a condition that can allow your thread to finish early

- Perform resource cleanups in an

ensure - Don’t use the

timeoutmodule - If you use

rack-timeout, you really should useterm_on_timeout - When you use threads, even implicitly (aka, via configuration in Puma, Sidekiq, Falcon and SolidQueue), you can end up in weird states from them shutting down. It should be rare, but misbehaving threads (very long transactions, runaway CPU) are the most likely to experience this. Pay attention to long running queries or runaway CPU usage and treat it as an important bug

- If you have something very critical that must properly cleanup 100% of the time, you need

handle_interrupt

(1) Don't kill threads

I’m watching you. Step away from that method, slowly, and no threads have to get hurt.

(2) Interrupt your thread safely

Instead of killing your thread, set it up to be interruptible. Most mature, threaded frameworks operate this way.

still_kickin = Concurrent::AtomicBoolean.new(true)

Thread.new do

while still_kickin.true?

# more work!

end

end

still_kickin.make_false

(3) Ensure cleanup

Whenever you need something to run before a method finishes, you should always use an ensure block. ensure is kind of like a method lifeguard - even if something goes wrong, it’s there for you. It’s the place code goes to ensure it’s run before the method finishes (even when an error is raised).

def read_some_data

read_it

close_it # bad

end

def read_some_data

read_it

ensure

close_it # good

end

We know ensure is not a silver bullet. Thread#raise and Thread#kill do not respect it. But you’re the most likely to clean things up using an ensure.

(4) Don’t use timeout

If you see this in code, be concerned:

require "timeout"

Timeout.timeout(1) do

# 😱

end

For some reason, the timeout gem itself doesn’t warn about any issues. But Mike Perham summarizes it best:

There’s nothing that exactly matches what timeout offers: a blanket way of timing out any operation after the specified time limit. But most gems and Ruby features offer a way to be interrupted - there is a repository called The Ultimate Guide to Ruby Timeouts which details everything you need to know. It shows you how to set timeouts safely for basically every blocking operation you could care about timing out. For instance, how to properly handle timeouts using the redis gem:

Redis.new(

connect_timeout: 1,

timeout: 1,

#...

)

The one piece mentioned in that repository you should leave alone: Net::HTTP open_timeout. Behind the scenes it uses the timeout module 🙅♂️. Leave the 60 second default, it should almost never impact you, and you’re probably worse off lowering it.

Primarily people use the timeout gem to manage IO timeouts. In the unlikely case you want to timeout CPU-bound code, it’s up to you to implement it in your processing.

(5) If you use rack-timeout, you really should use term_on_timeout

rack-timeout works similarly to the timeout module. And I already told you not to use that. So what gives? It will call raise on your threads - isn’t that bad?

The short answer is yes, it’s still bad.

But, rack-timeout is the only real option you have for timing out a web request in Puma. It’s meant as a last resort. From their docs:

rack-timeoutis not a solution to the problem of long-running requests, it’s a debug and remediation tool. App developers should track rack-timeout’s data and address recurring instances of particular timeouts, for example by refactoring code so it runs faster or offsetting lengthy work to happen asynchronously.

On top of that, you should have your own lower level timeouts set so that they would fire before rack-timeout.

You’ll want to set all relevant timeouts to something lower than

Rack::Timeout’sservice_timeout. Generally you want them to be at least 1s lower, so as to account for time spent elsewhere during the request’s lifetime while still giving libraries a chance to time out before Rack::Timeout.

The core issue of any thread raise/kill based solution is corrupted state. When using rack-timeout, you should be using term_on_timeout, ideally set to 1.

term_on_timeout will send a SIGTERM to the worker the thread is running in, which for most servers indicates a need for a graceful shutdown of that process - any potential corrupted state is isolated to that process and will be cleaned up once the process is shutdown.

term_on_timeout only works properly if you’ve got multiple processes serving your requests. And if you get lots and lots of timeouts, it could potentially cause performance problems. See the docs for proper configuration!

There is an alternative idea floating around out there of a way to achieve a “Safer Timeout”, at least in Rails apps:https://web.meetcleo.com/blog/safer-timeouts. Maybe I’ll detail it more in the future, but in the meantime, if you’re in a Rails app I would give it a read.

(6) Monitor your thread cost

Having threads that do not stop easily is a bug. If you’re seeing rack timeout errors, or jobs that can’t be shut down, track it and prioritize fixing it. Treat it like a bug and allocate time to improve it.

(7) Get a handle_interrupt on things

Thread.handle_interrupt is One Weird Trick Thread#kill Calls Don’t Want You To Know™. If we’re gonna discuss it, might as well go deep…

Thread.handle_interrupt

A thread can be externally “interrupted” by a few things:

Thread#killThread#raise- Your program being exited

- A signal, like Ctrl+C

handle_interrupt gives you the ability to control how your program reacts to 1-3. And it means you can define blocks of code which will guarantee their ensure blocks run.

handle_interrupt is a low-level interface and it’s also the one you are least likely to ever need. You’ll see it used in things like threaded web and job servers where low-level control and better cleanup guarantees are helpful. You’ll find examples of it in Sidekiq, the Async fiber scheduler, Homebrew, the parallel gem and more.

When you need the strongest guarantees possible about cleaning up your code in response to “interruption”, handle_interrupt is what you need.

Let’s look at a simple example:

class KnockItOffError < StandardError; end

t = Thread.new do

sleep 2

puts "done!"

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

Run that code 👆 and you’ll never see “done!” print. This is the same type of code we saw in the raise and kill section. What can handle_interrupt do for us?

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(KnockItOffError => :never) do

sleep 2

puts "done!"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# done!

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

Now we see “done!” printed! To be clear, the error will still be raised eventually. It can only impact the section it encloses, so the error will be raised right after.

What’s with the interface - what does KnockItOffError => :never mean? Let’s break it down:

handle_interrupttakes a hash. Each key is an exception class object, and each value is a symbol representing how to respond to the exceptionKnockItOffErrorin our example represents the class that will be handled. Descendants of the class are included, so it could beKnockItOffErroror any of its descendants.- There are three different symbols allowed as values:

:neverindicates that the exception will “never” interrupt any of the code inside of the block.:on_blockingindicates that the exception can only be raised during a “blocking” operation. This includes things like IO read/write,sleep, and waiting on mutexes. Anything that releases the GVL.:immediateindicates that the exception should be handled “immediately”. This is effectively the default behavior, so you would generally use this to re-apply an exception ignored at a higher level.

Based on that knowledge, let’s demonstrate a more complex example:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(KnockItOffError => :never) do

# KnockItOffError can "never" run here

Thread.handle_interrupt(KnockItOffError => :immediate) do

# KnockItOffError runs "immediate"ly here

sleep 2

puts "done!"

end

# KnockItOffError can "never" run here

ensure

puts "Can't touch this!"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# Can't touch this!

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

In this example, “done!” is never printed because it is in the :immediate block. But we successfully print out “Can’t touch this!” message in our ensure, because we’re within the :never block for KnockItOffError. ensure is now… ensured.

———

We’ve used :never and :immediate, what about :on_blocking?

i = 0

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :on_blocking

) do

1_000_000.times do

i += 1

end

puts "👋"

end

end

t.join(0.01)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 1

puts "i: #{i}"

puts thread_status(t)

# i: 1000000

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

Our increments work fine, as indicated by i being one million. But our puts is a “blocking” call so it gets the boot.

Should we have used a thread safe counter? Let’s try it again using Concurrent::AtomicFixnum from concurrent-ruby, and two threads. We should see i as two million afterwards:

require "concurrent"

i = Concurrent::AtomicFixnum.new(0)

def incrementing_thread(i)

Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :on_blocking

) do

1_000_000.times do

i.increment

end

puts "👋"

end

end

end

t = incrementing_thread(i)

t2 = incrementing_thread(i)

t.join(0.01)

t2.join(0.01)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

t2.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊👊"))

sleep 1

puts "i: #{i.value}"

puts thread_status(t)

puts thread_status(t2)

# i: 1237719

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊👊>>

Wait, why? i is 1237719? Why is i not two million? What blocked?!

📝 You’ll definitely see a different number. Sometimes you’ll see

1000000, sometimes you’ll see a higher number, but you’ll pretty much never see2000000

As it turns out, Concurrent::AtomicFixnum uses a Mutex by default. If a Mutex waits to acquire a lock it is considered a blocking operation! That means it qualifies for :on_blocking and the error gets raised.

As a specific fix for AtomicFixnum, if you install the concurrent-ruby-ext gem then you get native extensions which are lock-free, no longer use a Mutex, and properly run our code.

Once we install concurrent-ruby-ext, we properly get 2000000!:

# You ran `gem install concurrent-ruby-ext`

# It automatically loads if present

# ...

puts "i: #{i.value}"

puts thread_status(t)

puts thread_status(t2)

# i: 2000000

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊👊>>

But we also know that a Mutex or any other locking/waiting behavior can cause our :on_blocking interrupt to fire. So :on_blocking can have surprising behavior if some other internal of the code were to change later.

———

If the thread hasn’t started yet, handle_interrupt won’t help you. The error will be raised immediately in the thread, before handle_interrupt can be called:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :never

) do

puts "welcome!"

puts "later 👋"

end

end

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 1

puts thread_status(t)

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

———

What happens after handle_interrupt? Once the error is allowed to raise, code directly after it won’t run:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :never

) do

puts "can't stop won't stop"

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :immediate

) do

sleep 2

puts "this won't run"

end

puts "this won't run either"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# can't stop won't stop

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

But code after the inner handle_interrupt could run, it just depends on if the previous block raises. In this example, all of the code runs successfully because we don’t raise an error during the inner block:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :never

) do

puts "can't stop won't stop"

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :immediate

) do

sleep 2

puts "this won't run"

end

sleep 2

puts "this won't run either"

end

end

t.join(3)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

t.join # FIXME raises?

puts thread_status(t)

# can't stop won't stop

# this won't run

# this won't run either

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

But you’re better off guaranteeing code after the block runs. Use an ensure to make sure even if the inner block raises an error your code still runs:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :never

) do

puts "can't stop won't stop"

Thread.handle_interrupt(

KnockItOffError => :immediate

) do

sleep 2

puts "this won't run"

end

ensure

puts "this will consistently run"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.raise(KnockItOffError.new("👊"))

sleep 0.1

puts thread_status(t)

# can't stop won't stop

# this will consistently run

#<ThreadStatus status="failed w/ error: 👊" error=#<KnockItOffError: 👊>>

———

Can we even stop the unstoppable Thread#kill? Yep! From the Thread.handle_interrupt docs:

For handling all interrupts, use Object and not Exception as the ExceptionClass, as kill/terminate interrupts are not handled by Exception.

So we can handle it - but we have to use Object, which looks a bit odd but works well:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(Object => :never) do

sleep 2

puts "done!"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.kill

t.join

puts thread_status(t)

# done!

#<ThreadStatus status="finished" error=nil>

The reason for this odd syntax is that the kill/terminate interrupts are internally handled not as Exception instances, but as integers. That means this would also work:

t = Thread.new do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

Integer => :never

) do

sleep 2

puts "done!"

end

end

t.join(1)

t.kill

t.join

puts thread_status(t)

# done!

#<ThreadStatus status="finished" error=nil>

Still, you’re better off using Object to avoid the implementation detail.

———

Can we stop the timeout gem from raising at a bad time using handle_interrupt? The Thread API docs used to specifically use timeout as a use-case for handle_interrupt, but there’s a non-determinism bug around thread reuse within the timeout gem.

So once again, don’t use the timeout gem.

I removed the example from the docs because it’s too broken, so on Ruby 3.4+, the docs no longer mention handle_interrupt with the timeout gem.

———

We’ve looked at many handle_interrupt examples - what do real gems use it for?

In the async gem it uses handle_interrupt to ignore SignalException while it shuts down its child tasks:

# Stop all children, including transient children, ignoring any signals.

def stop

Thread.handle_interrupt(::SignalException => :never) do

@children&.each do |child|

child.stop

end

end

end

In sidekiq, when it has gracefully attempted a shutdown and is forcing threads to finish, it raises a special error. That error extends Interrupt, which means most rescue blocks will not capture it because it is a child of Exception rather than StandardError:

module Sidekiq

class Shutdown < Interrupt; end

end

# later...

t.raise(Sidekiq::Shutdown)

To avoid Sidekiq::Shutdown breaking everything (including its own internal code), Sidekiq also uses handle_interrupt to ignore the error in a small piece of shutdown code:

IGNORE_SHUTDOWN_INTERRUPTS = {Sidekiq::Shutdown => :never}

ALLOW_SHUTDOWN_INTERRUPTS = {Sidekiq::Shutdown => :immediate}

def process(uow)

jobstr = uow.job

queue = uow.queue_name

#... process logic

ack = false

Thread.handle_interrupt(

IGNORE_SHUTDOWN_INTERRUPTS

) do

Thread.handle_interrupt(

ALLOW_SHUTDOWN_INTERRUPTS

) do

dispatch(...) do |inst|

config.server_middleware... do

execute_job(...)

end

end

ack = true

rescue Sidekiq::Shutdown

# Had to force kill this job because it didn't finish

# within the timeout. Don't acknowledge the work since

# we didn't properly finish it.

ensure

if ack

uow.acknowledge

end

end

end

If this section hasn’t been enough for you, Ben Sheldon gives some additional interesting examples In his article Appropriately using Ruby’s thread handle_interrupt.

The way you ensure success

I’m pretty confident, started from scratch, Ruby would not be implemented with raise and kill again. I don’t know _which _ model they would choose - but something like a Java interrupt would be a good start. And minimally, making all ensure blocks uninterruptable, as well as all finalizers. I didn’t even get into finalizers - they’re a less common, but also important area that you really don’t want to interrupt.

Ruby is one of the only programming languages that lets you kill a thread from outside of the thread. It’s powerful, but mostly, it’s dangerous. It’s one of the sharpest tools available to you, and it should be used sparingly, or ideally not at all.

In threaded code, the best offense is a good defense:

- Consider how to safely manage your threads. If your thread is going to do a lot of work, or expensive work, make sure you have an escape hatch (like a boolean check for interrupts)

- Treat performance issues like a bug. If you have threads that are hogging resources and timing things out, you need to fix them.

killing them is not a long-term answer - Ultimately, there is no way to guarantee the safety of your code 100% of the time. The OS could kill your program. Your server could get unplugged. You’re always going to have edge cases that you can’t foresee. But control what you can, and be aware of what can go wrong.

Now go forth, armed with the knowledge on what to do when good threads go bad.

-

Unless you’re in SQLite, where apparently N+1 queries are a virtue 😲 https://www.sqlite.org/np1queryprob.html ↩︎

-

In general, you shouldn’t do this directly ↩︎

-

And processes.

Or use Falcon. See me later in the series when we talk about Fibers 😏 ↩︎

-

There’s a small mention about how to handle Timeout errors, but it doesn’t explain much or warn at all ↩︎